A place for transitions

The fall of 1999 was my most difficult semester of college. I was a junior majoring in mechanical engineering at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and with the dean’s approval I had an overloaded schedule of seven courses. That would have made for a challenging term under the best of circumstances. In September I tore a ligament in my right knee while playing flag football, requiring surgery and six months of physical therapy. And on top of all that there was a secret crush.

There was also a silver lining: spring offered a break from classes. I had opted for the school’s cooperative education program, providing two semesters of paid, full-time work experience in engineering offices. The late ‘90s tech bubble hadn’t burst yet and the economy was booming. I was getting three or four interviews a week and struggling to find time for them between classes, homework, and rehab sessions. Nevermind sleep. I barely managed four hours a night that fall.

Walking out of my last exam in December was like seeing the sky for the first time after spending months underground. I escaped that semester with a 3.3 GPA, the lowest of my college career. Disappointed then, with twenty years’ hindsight it seems nothing short of heroic. A few weeks earlier, I had even managed to build up all the courage I could muster and confess my feelings to my crush. Hers were not mutual.

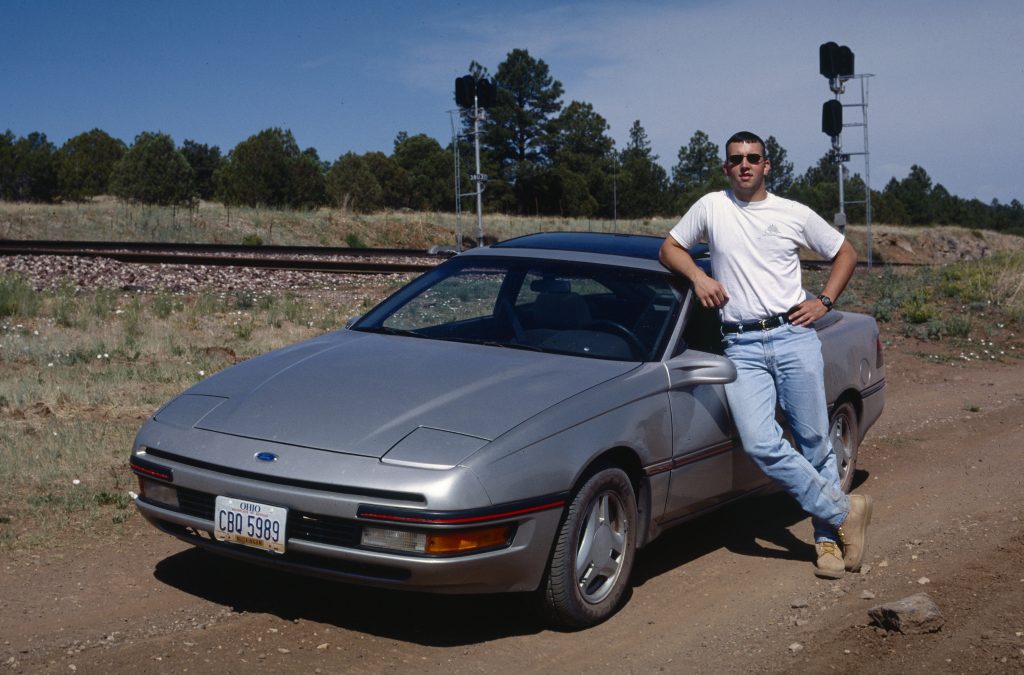

The interviews paid off with some half-dozen job offers, all in Cleveland save one. Cleveland had nearly broken me that fall. After spending Christmas with my family and ringing in Y2K with high school friends, I packed my ‘91 Ford Probe and pointed it southwest, for Arizona.

I wish I could say there ensued a grand adventure, and that as a budding photographer I blossomed into an artist who came back at the end of the summer with hundreds of incredible photographs. While it was an adventure, it was hardly grand in the ways I wish, and nearly all of the photographs are forgettable.

Even the drive out was a far cry from being my first solo road trip. My grandparents came, too, providing an escort and moving assistance in their pickup. I was glad for their help then, and I’m so grateful for that time together now. They had introduced me to the West from the backseat of their Dodge the summer I was twelve, my only prior jaunt to the far shore of the Mississippi. The drive to Arizona would be our last big road trip together. Grandma traded off riding shotgun with Grandpa and me. Had it not been for her calming presence in my passenger’s seat, I may not have made it across the wind-whipped Texas panhandle in heavy traffic on I-40.

What happened in Arizona over those first seven months of 2000 was a lot of real life. I was a twenty-year-old living independently for the first time, away from home, away from my college community. I worked forty-hour weeks, paid all my own bills, and did all my own chores. Adventure had to fit into neat packages on the weekends.

My boss had suggested getting an apartment in Tempe surrounded by student life at Arizona State, but that was the very scene I had come to escape. I found a furnished one-bedroom in a quiet complex just a few miles from my office in Glendale.

Phoenix is the easiest city I’ve ever navigated. It’s a near-perfect grid, eight blocks to the mile in each direction for miles upon miles. The only major exception is Grand Avenue, which cuts a diagonal running northwest from downtown. It’s diagonal because it follows the Santa Fe Railway, today part of BNSF. Both the tracks and the road cross two other streets at every intersection. When a mile-long freight train rolls through, the entire northwest quadrant of the greater Phoenix metropolitan area grinds to a standstill on nearly every major street except for Grand.

I crossed those tracks twice a day on my way to and from work, and many mornings I’d see a piggyback train getting ready to leave behind four or five big diesels. That train ran on Saturdays, too, and several times I followed it out of town, sometimes going all the way to Williams where the Phoenix branch connects with the double-track main line running from Chicago to Los Angeles. Route 66 follows those tracks, and on the strip in Flagstaff you could still get a motel room for $25 a night. Cross-country freights thundered by every fifteen minutes and the snow-capped San Francisco Peaks towered in air that was crisp and clear, perfumed by juniper and pine. I drank deeply of it all.

South of Phoenix, the desert–the real desert with jackrabbits, rattlesnakes, and perfect saguaros–rolled out in dizzying 360-degree panoramas of aridity. Union Pacific’s Sunset Route stretched across that desert, nearly as busy as the BNSF with its own long-haul trains heading to and from LA and Long Beach. I made friends with a fellow train photographer in Phoenix, and occasionally we explored that line together. But most of my trips were on my own.

Over Memorial Day weekend, two college friends came to visit. They were outside my regular circle. Our connection was not the happenstance of residence hall assignments but deep mutual interests. I slept on top of their Jeep under skies of endless stars and they took me to railroads I never would have seen on my own. There was the fan-favorite Apache with its vintage Alco diesels, but the one that truly captivated me was a Union Pacific (former Southern Pacific) branch line on the New Mexico border.

The Clifton Branch leaves the Sunset Route at Lordsburg, New Mexico, and cuts northwest across desert and farmland irrigated by the Gila River. It would be unremarkable save for the last five miles into Clifton, a twisting descent through tunnels and a horseshoe curve to the banks of the San Francisco River. In a tiny yard hemmed in by the river on one side and a sheer cliff on the other, the Clifton Local would swap cars with the private Phelps-Dodge Railroad. Their train came down an even steeper grade from Morenci, home to one of the largest copper mines in the world. I was smitten, and in the two months I had left in Arizona after Memorial Day, I returned four times. The trip was more than 200 miles each way, and once, on a lonely stretch of US 70, I pushed my car over 100 miles an hour for the only time in my life.

At the end of July, when daytime highs routinely reached the 110s, my parents drove out in their pickup, helped me pack up that one-bedroom apartment, and drove with me back to Ohio. Fully recovered from that brutal fall semester, I was ready to return to the life I had put on hold in Cleveland. Yet I was much changed from the person I had been seven months earlier, and college would not be the same as it had been before.

Recently, I went back through the slides I shot in Arizona to organize and digitize them. I kept less than half, and most of those for sentimentality rather than aesthetics. It was hard to be reminded of just how bad I had been at photography then. Other memories hurt, too. So few of my slides bore dates on Sundays, a reminder of both how desperately I had still been clinging to the religion of my childhood and yet another stillborn romance that sputtered but did not spark in the young adult group at that church. I wish now that more of my Saturday outings had been weekend-long camping and photography excursions. They may not have led to better pictures, but I’d like to think I might have etched a few more memories of that evocative Southwest landscape out beneath the clarity of the desert night sky.

Arizona may not have been the adventure I was seeking, but it was the next step I needed. I discovered there how much I enjoy photography and how content I could be on my own in that pursuit. Without even realizing it, I’d been trying too hard to conform to mainstream interests and trading away a very important part of myself in the process. No wonder my attempts at romance never blossomed.

Arizona is not where I made great photographs, but it is the place where I started to learn how to seek them. It was where that passion stirred and began to awaken, and it would not return to slumber even after I returned to my familiar campus community in Cleveland. There was a new restlessness inside me that welled up with every weekend social plan, a dynamic tension between spending time with friends and following my own call. In twenty years it has not abated. When I look at my slides from Arizona, I do not find great photographs. But if I look carefully, beyond the harsh light and insipid compositions, I can find traces of a young man, for the first time, beginning to find himself.